mercredi 21 octobre 2015

mardi 20 octobre 2015

lundi 19 octobre 2015

dimanche 18 octobre 2015

jeudi 15 octobre 2015

Apple's recent concessions in China have a pattern

by Scott Cendrowski

OCTOBER 13, 2015, 10:53 AM EDT

OCTOBER 13, 2015, 10:53 AM EDT

Apple Inc. is becoming a proxy for what U.S. tech companies must do to stay relevant (and profitable) in China.

Over the weekend news broke that Apple’s news app was blocked by Apple itself in mainland China in what appeared to be an act of self-censoring before Apple can figure out how to appease the Chinese government’s strict censorship standards while offering news in its most important growth market.

“This “China Kill Switch” is currently limited to disabling the News App and Apple Maps, but it is easy to imagine a Chinese government official asking Apple to extend that ability to other Apps and services on our iPhones,” an entrepreneur who first noticed the blockage, Larry Salibra, CEO of Pay4Bugs, wrote on his website.

But this isn’t the only move Apple has made to comply with Chinese government’s demands. Instead, it was the latest in a string of decisions that are shaping up as a how-to if you’re an American tech company appealing to Chinese consumers.

Here are decisions Apple made specific to its China business, its second largest market.

Storing user data in China

Last year, Apple started storing personal data on servers located in mainland China. It was notable because Google Inc. GOOG 0.87% had earlier declined to store users’ data in China due to privacy concerns. Even though Applesaid user info is encrypted and that China Telecom, the third largest of the state-owned wireless carriers that runs the servers, wouldn’t have access to the data, foreign analysts tracking the Chinese market were skeptical that Apple wouldn’t need to share data at the Chinese government’s behest.

Security audits

Earlier this year, Apple acquiesced to the Chinese government’s demands for security reviews of its products. The state-run Beijing News reported in January that Tim Cook had met with China’s internet czar Lu Wei in December and said Apple would cooperate with security assessments of its iPhones, iPads, and Mac computers. Analysts opined that Apple might be forced to share sensitive source code as part of the checks.

Beats 1 live radio station

The entrepreneur who discovered the self-censored News app over the weekend also points out that Apple Music in China doesn’t include the live radio station Beats 1. On itspromotional site, Apple calls Beats 1 “a truly global listening experience” and says “No matter where you are or when you tune in, you’ll hear the same great programming as every other listener.” That is not true if you live in Apple’s second largest market.

Censor App store

Like Amazon and other sellers in China, Apple also censors its App and book stores to meet the Communist Party’s demands. For instance, in 2013, Apple removed an app from its store that provided access to books about Tibet and Xinjiang among others.

In its latest earnings report, Apple said China sales grew 112% from the previous year in China. Cook later said the Chinese iPhone market grew 75%. Apple appears to be doing everything it can to protect business in its most important growth market.

China’s Great Game: Road to a new empire

October 12, 2015 7:24 pm

By Charles Clover and Lucy Hornby

By Charles Clover and Lucy Hornby

“The granaries in all the towns are brimming with reserves, and the coffers are full with treasures and gold, worth trillions,” wrote Sima Qian, a Chinese historian living in the 1st century BC. “There is so much money that the ropes used to string coins together rot and break, an innumerable amount. The granaries in the capital overflow and the grain goes bad and cannot be eaten.”

He was describing the legendary surpluses of the Han dynasty, an age characterised by the first Chinese expansion to the west and south, and the establishment of trade routes later known as the Silk Road, which stretched from the old capital Xi’an as far as ancient Rome.

Fast forward a millennia or two, and the same talk of expansion comes as China’s surpluses grow again. There are no ropes to hold its $4tn in foreign currency reserves — the world’s largest — and in addition to overflowing granaries China has massive surpluses of real estate, cement and steel.

After two decades of rapid growth, Beijing is again looking beyond its borders for investment opportunities and trade, and to do that it is reaching back to its former imperial greatness for the familiar “Silk Road” metaphor. Creating a modern version of the ancient trade route has emerged as China’s signature foreign policy initiative under President Xi Jinping.

“It is one of the few terms that people remember from history classes that does not involve hard power . . . and it’s precisely those positive associations that the Chinese want to emphasise,” says Valerie Hansen, professor of Chinese history at Yale University.

Xi’s big idea

If the sum total of China’s commitments are taken at face value, the new Silk Road is set to become the largest programme of economic diplomacy since the US-led Marshall Plan for postwar reconstruction in Europe, covering dozens of countries with a total population of over 3bn people. The scale demonstrates huge ambition. But against the backdrop of a faltering economy and the rising strength of its military, the project has taken on huge significance as a way of defining China’s place in the world and its relations — sometimes tense — with its neighbours.

Economically, diplomatically and militarily Beijing will use the project to assert regional leadership in Asia, say experts. For some, it spells out a desire to establish a new sphere of influence, a modern-day version of the 19th century Great Game, where Britain and Russia battled for control in central Asia.

“The Silk Road has been part of Chinese history, dating back to the Han and Tang dynasties, two of the greatest Chinese empires,” says Friedrich Wu, a professor at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore. “The initiative is a timely reminder that China under the Communist party is building a new empire.”

According to former officials, the grand vision for a new Silk Road began life modestly in the bowels of China’s commerce ministry. Seeking a way to deal with serious overcapacity in the steel and manufacturing sectors, commerce officials began to hatch a plan to export more. In 2013, the programme received its first top-level endorsement when Mr Xi announced the “New Silk Road” during a visit to Kazakhstan.

Since the president devoted a second major speech to the plan in March — as concerns over the economic slowdown mounted — it has snowballed into a significant policy and acquired a clunkier name: “One Belt, One Road”. The belt refers to the land trade route linking central Asia, Russia and Europe. The road, oddly, is a reference to a maritime route via the western Pacific and Indian Ocean.

In some countries Beijing is pushing at an open door. Trade between China and the five central Asian states — Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan — has grown dramatically since 2000, hitting $50bn in 2013, according to the International Monetary Fund. China now wants to build the roads and pipelines needed to smooth access to the resources it needs to continue its development.

Mr Xi started to offer more details about the scheme earlier this year with an announcement of $46bn in investments and credit lines in a planned China-Pakistan economic corridor, ending at the Arabian Sea port of Gwadar. In April, Beijing announced plans to inject $62bn of its foreign exchange reserves into the three state-owned policy banks that will finance the expansion of the new Silk Road. Some projects, already on the drawing board, seem to have been co-opted into the new scheme by bureaucrats and businesspeople scrambling to peg their plans to Mr Xi’s policy.

“They are just putting a new slogan on stuff they’ve wanted to do for a long time,” says one western diplomat.

“It’s like a Christmas tree,” says Scott Kennedy, deputy director at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “You can hang a lot of policy goals on it, but no one has done a proper economic analysis. The government money they are putting in is not enough; they hope to bring in private capital, but would private capital want to invest? Will it make money?”

As well as offering a glimpse of China’s ambition, the new Silk Road presents a window into how macroeconomic policy is made in Beijing — often on the hoof, with bureaucrats scurrying to flesh out vague and sometimes contradictory statements from on high. “Part of this is top down, part of this is bottom up, but there is nothing in the middle so far,” says a former Chinese official.

“The rest of the bureaucracy is trying to catch up to where Xi has planted the flag,” says Paul Haenle, director of the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center in Beijing. “This is something that Xi announces and then the bureaucracy has to make something of it. They have to put meat on the bones.”

Some clues emerged in March when the powerful National Development and Reform Commission, China’s central planning body, published a clunky document, “Visions and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-century Maritime Silk Road”. It provides a great deal of detail in some places — such as which book fairs will be held — but is patchy in others, like which countries are included. Peru, Sri Lanka and even the UK are included in some versions of semi-official maps but left out of others.

A complete list appears to exist, however. On April 28 the commerce ministry announced that Silk Road countries account for 26 per cent of China’s foreign trade, a remarkably precise statistic. However, a request from the Financial Times for more specific details on the list of nations went unanswered.

There is also no indication yet of how it will be run — through its own bureaucracy, or as separate departments in different ministries and policy banks. With foreign governments and multinational banks eagerly following the Delphic utterances from Beijing to understand what it means, the vagueness and confusion has not gone unnoticed.

“If we want to talk to the Silk Road,” says a diplomat from a neighbouring state, “we don’t know who to call.”

As the country’s economic interests expand abroad, its massive security apparatus and military will probably be pulled into a greater regional role. China has no foreign military bases and steadfastly insists that it does not interfere in the domestic politics of any country. But a draft antiterrorism law for the first time legalises the posting of Chinese soldiers on foreign soil, with the consent of the host nation.

China’s military is also eager to get its share of the political and fiscal largesse that accompanies the new Silk Road push. One former US official says he was told by senior generals in the People’s Liberation Army that the One Belt, One Road strategy would have a “security component”.

Projects in unstable areas will inevitably test China’s policy of avoiding security entanglements abroad. Pakistan has assigned 10,000 troops to protect Chinese investment projects, while in Afghanistan, US troops have so far protected a Chinese-invested copper mine.

Port construction in countries like Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan has led some analysts to question whether China’s ultimate aim is dual-use naval logistics facilities that could be put into service controlling sea lanes, a strategy dubbed the “String of Pearls”.

Achieving the trust of wary neighbours including Vietnam, Russia and India is not a given, and is consistently being undermined by sustained muscle flexing by China elsewhere. In the South China Sea, for example, naval confrontations have increased in the face of aggressive maritime claims by Beijing.

Exporting overcapacity

Lenin’s theory that imperialism is driven by capitalist surpluses seems to hold true, oddly, in one of the last (ostensibly) Leninist countries in the world. It is no coincidence that the Silk Road strategy coincides with the aftermath of an investment boom that has left vast overcapacity and a need to find new markets abroad.

“Construction growth is slowing and China doesn’t need to build many new expressways, railways and ports, so they have to find other countries that do,” says Tom Miller of Beijing consultancy Gavekal Dragonomics. “One of the clear objectives is to get more contracts for Chinese construction companies overseas.”

Like the Marshall Plan, the new Silk Road initiative looks designed to use economic treats as a way to address other vulnerabilities. China’s western frontiers and its central Asian neighbours are home to vast reserves of oil and gas. The Xinjiang region, sitting on some of China’s largest energy reserves and crucial to the Silk Road project, is also home to a restive Muslim Uighur population that is culturally Turkish, far poorer than the citizens of coastal China and seeking a break with Beijing. The region has been the scene of serious outbreaks of violence in recent years.

A push into central Asia will partly fill the vacuum left by the retreat of Moscow after the cold war, followed by Washington’s military pullback from Afghanistan next year. With Beijing saying it is facing a rising terrorist threat, stabilising the wider region is a priority.

But, in doing so, China will inherit the same chicken and egg problem that has plagued the US in its “nation building” attempts — having to ask whether security and stability is a pre-requisite for economic development, or whether, as Beijing appears to believe, it can pacify local conflicts with a sea of investment and infrastructure spending.

Combating radical Islam

If this approach does not work, China will be faced with some grim alternatives — either turn tail and leave, or risk getting bogged down in security commitments and local politics. It has made clear that it does not want to replace the US in Afghanistan nor does it see itself as a regional policeman. “China will not fall into the same mistakes,” says Jia Jinjing, a specialist on south Asia at Beijing’s Renmin University.

Economic development, strategists in Beijing argue, will remove the appeal of radical Islam in China and Pakistan, Afghanistan and central Asia. But critics note that culturally insensitive policies, an enormous security presence and economic strategies that benefit Chinese communities at the expense of locals have so far only escalated tensions in Xinjiang, the desert region that has 22 per cent of China’s domestic oil reserves and 40 per cent of its coal deposits.

Roads and pipelines across Pakistan and Myanmar will ultimately allow China to avoid another strategic vulnerability — the chokepoint of the Strait of Malacca, through which about 75 per cent of its oil imports pass. Already, half of China’s natural gas arrives overland from central Asia, thanks to an expensive strategy by Mr Xi’s predecessors to cut dependence on seaborne imports.

While some neighbours will welcome the investment, it is less clear they will want China’s overcapacity. Many have unemployment and underperforming steel mills of their own, or ambitions to develop their own industry rather than import someone else’s.

Large-scale investment could also trigger concerns about opening the floodgates to Chinese economic dominance — as it has done in Myanmar and Sri Lanka — and, by extension, political influence. But China is hoping the lure of massive spending will prove too great an incentive for its neighbours to resist.

“They [Beijing] don’t have much soft power, because few countries trust them,” says Mr Miller. “They either can’t or don’t want to use military power. What they have is huge amounts of money.”

Additional reporting by Michael Peel and Ma Fangjing

China steps up hunt for perpetrators of deadly Xinjiang attack

Tom Mitchell in Aksu and Christian Shepherd in Beijing

October 11, 2015 6:59 am

October 11, 2015 6:59 am

Authorities in northwestern China have cordoned off an area twice the size of New York City as their hunt for the perpetrators of one of the region’s deadliest ever attacks enters its fourth week.

Residents of Baicheng county in Xinjiang province say that at least 60 people, most of them migrant coal miners from across the country, were knifed to death in a September 18 attack on the Sogan coal mine.

Most of Baicheng’s residents are Muslim Uighurs, a small number of whom have taken up arms against a government they believe is deliberately eroding their religious and cultural heritage by encouraging a wave of Han Chinese migration.

Xinjiang has long been a strategic priority for the Chinese government because of its natural resources, including the country’s largest coal reserves, and its proximity to even bigger energy sources in Central Asia. It is also a key component of President Xi Jinping’s “New Silk Road” strategy, aimed at enhancing Eurasian infrastructure links.

“More than 60 people were killed at the mine,” one Baicheng resident told the Financial Times by telephone. “Military helicopters and drones are still searching the mountains for the attackers.”

The person asked not to be named, citing warnings from local officials: “They said we shouldn’t embarrass China and Baicheng by talking to foreign journalists. But I think they are really worried that they will be punished for incompetence if too much information gets out. How can they not have caught anyone after such a big attack?”

The helicopters and drones are operating out of the airport at Aksu, the largest city in the area. Police have established checkpoints on all roads leading to Baicheng, which covers an area of about 16,000 sq km. Heavily armed police are posted behind sandbag bunkers at each road block, providing cover for their colleagues who perform identification and weapons checks on all people entering the area.

An FT reporter was turned back at one of the checkpoints on Saturday. “You can’t go to Baicheng or the coal mine because of the counter-terrorism operation,” one police officer said. He declined to comment further on last month’s attack, which was first reported by Radio Free Asia’s Uighur-language service, or the continuing search. According to RFA, last month’s victims included at least five police officers who responded to the incident.

Despite the information blackout, the attack is the talk of Aksu, where residents speculate that the death toll may exceed 100.

The deadliest known outbreak of intercommunal tensions in Xinjiang occurred in 2009 in the region’s capital, Urumqi, when mob violence claimed the lives of 197 people, most of them Han Chinese.

Organised attacks on symbols of the state, especially police stations, have been common for years in Xinjiang. But beginning in March last year, alleged Uighur “separatists” began to deliberately target civilians in well coordinated assaults, at a train station in the city of Kunming in southwestern China, and a food market in Urumqi.

Last month’s Baicheng massacre would appear to fit this pattern as most of the victims were migrant coal miners, but it is also possible that apparently sectarian-motivated attacks in Xinjiang could instead stem from disputes over pollution or land.

Nick Holdstock, who has written several books about Xinjiang, said: “A number of these [recent] incidents have differed from previous ones in that they seemed to target civilians and involved a degree of planning. But we should be careful not to assume that people in different regions in Xinjiang share the same grievances simply because of their shared ethnicity. The concerns of Uighur businessmen may not be the same as Uighur farmers.”

The Chinese government claims that shadowy terrorist groups and religious extremists are responsible for much of the violence, although such claims are difficult to confirm independently.

Jeremy Corbyn to raise China's human rights record at state banqu

Rowena Mason

Wednesday 14 October 2015 10.52 EDT

Wednesday 14 October 2015 10.52 EDT

Jeremy Corbyn will attempt to challenge the Chinese on their human rights record when he attends a state banquet to be held by the Queen for the country’s president, Xi Jinping, next week.

There had been speculation that Corbyn, as a republican, might send a substitute to the banquet but Labour has since confirmed he will attend Buckingham Palace for the ceremonial dinner.

A spokesman for the Labour leader said: “He will be using the opportunity next week to raise the issue of human rights. There are meetings being discussed, and if he gets private meetings he will be raising it at those meetings. That is the right thing to do.”

It is Corbyn’s first invitation to a Buckingham Palace state dinner in his role as leader of the opposition. He was unable to make a previous visit to the royal residence to be sworn in to the privy council, although he is expected to do so soon to receive classified security briefings.

Since becoming Labour leader, Corbyn has taken a strong stance on the raising of human rights abuses with other states, and successfully pressed David Cameron to drop a prisons deal with Saudi Arabia.

China has been criticised by campaigners for jailing critics of its communist government, media censorship and restricting personal freedom. However, George Osborne stressed economic issues, rather than human rights, when he visited China for a trade trip last month.

The chancellor said at the time: “This is primarily an economic and financial dialogue. We are two completely different political systems and we raise human rights issues, but I don’t think that is inconsistent with also wanting to do more business with one-fifth of the world’s population.”

The Global Times, a Chinese state-run newspaper, praised Osborne for being “the first western official in recent years who focused on business potential rather than raising a magnifying glass to the ‘human rights issue’”.

Osborne had been urged to raise the persecution of the Uighur minority during his trip to the Xinjiang capital, Urumqi, a year after a court in the city imprisoned the government critic Ilham Tohti for life on charges of inciting separatism.

Kate Allen, UK director of Amnesty International, criticised the chancellor’s failure to mention Tohti’s case and “sending the signal that the UK is willing to compromise its human rights values”.

The UK supported an EU statement that raised concerns about China’s detention of more than 100 activists and lawyers in July and called for their release.

Hugo Swire, a Foreign Office minister, said last month he “remains concerned by the restrictions placed on Christianity in China”, citing the closure or demolition of churches, removal of crosses from buildings, and reports that individuals are harassed or detained for practising their beliefs.

China’s Great Game: New frontier, old foes

Tom Mitche

October 13, 2015 7:16 pm

October 13, 2015 7:16 pm

As one of the world’s most remote and landlocked regions, Xinjiang is not high on the itinerary for foreign dignitaries visiting China. So when George Osborne, the UK’s chancellor, made a special request to visit the territory last month, it was unexpected and controversial — but also welcomed by the Chinese government.

Xinjiang is a linchpin in President Xi Jinping’s “new Silk Road” project, which aims to revive the ancient trade routes that connected imperial China to Europe and Africa. Mr Osborne described his detour to the capital, Urumqi, as proof of his government’s determination to be “bold abroad”. It was indeed a bold choice, and not just because of the region’s remoteness.

A vast region about three times the size of France, Xinjiang — literally “new frontier” — is home to a violent insurgency that is a frequent source of frustration and embarrassment for Beijing. The unrest burst on to the global stage in 2009 when thousands of Muslim Uighurs — the region’s biggest ethnic group — went on a rampage in Urumqi. The riot left 197 people dead, most of them Han Chinese.

A steady pattern of low-level violence has followed. As if on cue, while Mr Osborne visited a property investment company and football academy in Urumqi, a manhunt was under way for the perpetrators of a massacre at a coal mine in southern Xinjiang that left more than 50 people dead.

For the architects of Mr Xi’s Silk Road project, the slaughter at the Sogan coal mine — which neither the Chinese government nor state media have acknowledged — was a reminder of the challenges that lie ahead as Beijing begins playing a “Great Game” of its own in central Asia and beyond.

To realise this dream of an infrastructure-led revival of commerce and prosperity across the Eurasian land mass, the Chinese government will first have to tame its own Wild West. At the moment, however, it is refusing to budge from policies that seem only to be fanning the flames of ethnic unrest.

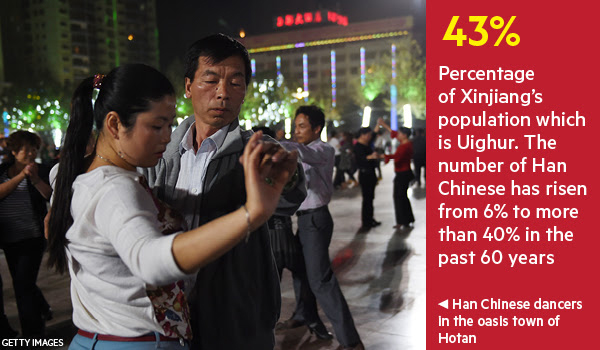

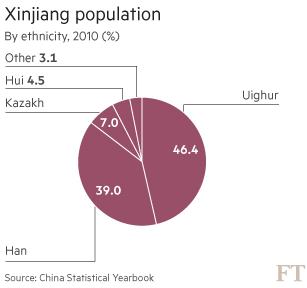

Over the past 60 years, the Han, China’s dominant ethnic group, have increased their proportion of Xinjiang’s population from 6 per cent to more than 40 per cent, fuelling widespread resentment among Uighurs who see the influx as part of a deliberate attempt by Beijing to dilute their community’s religious and cultural identity.

“Xi Jinping sees Xinjiang as absolutely critical for his agenda. It’s not just about security and solving the Uighur issue, it’s also about building this new Silk Road economic belt,” says James Leibold, a China scholar at La Trobe University in Melbourne. “The party needs to convince a weary Han public and foreign governments that the anti-terror campaign has succeeded, and shift the narrative to Xinjiang as the gateway to the new Silk Road and the countless opportunities [that] await those willing to invest in the region.”

Gateway to resources

It is easy to see why Beijing is fixated on Xinjiang. The region holds China’s largest natural gas reserves, 40 per cent of its coal and 22 per cent of its oil. More importantly, it is the gateway to even larger energy deposits in central Asia. Huge investments have been made in infrastructure needed to tap those resources, including an oil pipeline running from Kazakhstan and a natural gas pipeline from Turkmenistan.

The oil and gas pipelines, which came online before Mr Xi came to power, represented the first part of a three-stage transaction that sends natural resources to China in return for payments that central Asian nations then use to buy everything from Chinese consumer goods to capital equipment.

Beijing very much wants these trade patterns to expand, especially as it seeks to secure energy sources that — unlike Middle Eastern oil — do not need to pass through the vulnerable Strait of Malacca and volatile South China Sea. But Mr Xi’s vision has an added emphasis on cross-border high-speed railways and motorways, such as the Karakoram highway connecting southern Xinjiang and Pakistan, which should foster a broader range of commerce.

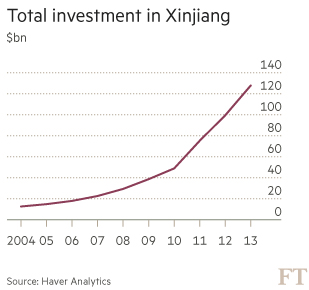

Beijing has been pouring cash into Xinjiang, which recorded expenditures of Rmb1.3tn ($157bn) last year against revenues of just Rmb454bn. State financial transfers to the region rose to Rmb1.1tn in the 2009-14 period, almost double what had been remitted over the previous 54 years, while richer provinces have invested another Rmb54bn in 4,900 aid projects.

Mr Xi is effectively “doubling down” on his predecessors’ bet that big investments in economic development — and regional security forces — will quell the unrest in Xinjiang, Mr Leibold says.

While Beijing maintains it is combating what it calls “the three forces” of ethnic separatism, religious extremism and terrorism in the region, others argue that the violence stems from a government strategy that has alienated Xinjiang’s Uighur community. Of the just 23m people living in the arid but energy-rich region, Uighurs account for about 43 per cent of the population — down from as much as 90 per cent before the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

Many of Xinjiang’s cities are plastered with crude, billboard-sized cartoons depicting the hell that awaits those who succumb to Islamic fundamentalism — and the heaven for those who embrace a “unified and multi-ethnic” China. At a food market in Aksu, a hub for a larger agricultural and mining area, a Uighur trader waves a dismissive hand at the warnings. “That propaganda is all rubbish,” he says in heavily accented Chinese. “There is no freedom in Xinjiang.”

The inability of so many Uighurs to attain even basic proficiency in Chinese — most speak Uighur, a language related to Turkish — is one of the reasons they are passed over for the best jobs, and why Han migrants are often better placed to seize opportunities. In a visit to the region last year, Mr Xi acknowledged that “resource exploitation has enriched large enterprises and entrepreneurs rather than the local area and its people”.

The Chinese government, however, says there is no connection between the violence and its own policies in Xinjiang. Instead, it blames terrorists and religious extremists, some of them allegedly funded or inspired by foreign groups whose aim is to “split up” China.

“These violent and bloody crimes show clearly that the perpetrators are anything but representatives of ‘national’ or ‘religious’ interests,” the State Council said last month in a white paper marking the 60th anniversary of the establishment of Xinjiang as a special autonomous region. “They are a great and real threat to ethnic unity and social stability in Xinjiang.”

A militarised region

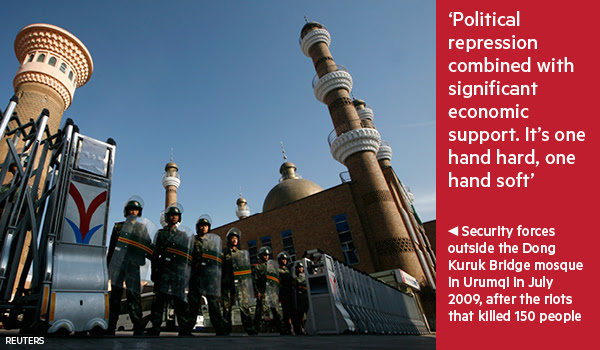

An alternative explanation is that Beijing is now confronted with an entirely homegrown problem rooted in flawed policies that the government refuses to acknowledge, let alone correct. As a result, some critics believe the region risks a downward spiral in which violence begets an ever more militarised response that begets additional violence — all at a time when Xinjiang is more central than ever to the ruling Communist party’s larger geopolitical objectives.

Xinjiang now resembles a militarised state, with a blatant police and military presence. While most experts say its insurgency does not qualify as a “low-intensity conflict”, evidence of the potential for violence is everywhere.

An Urumqi street where five alleged Uighur separatists killed 31 people last year is a bar area by night, with private armed guards protecting each establishment. People entering Urumqi’s People’s Park, a popular recreation area in the city centre, are searched by soldiers in stab-resistant vests and helmets while armed police patrol the park grounds in groups of five or more.

Feng Guoping, a Han Chinese resident of Urumqi, says “everything has changed since July 5”, referring to the date of the city’s deadly 2009 riots. “Now we are on guard against the Uighurs and they are on guard against us,” adds Mr Feng, whose parents moved to Urumqi from Jiangsu province when he was 11 because they thought their son would have a better chance at getting into university in Xinjiang.

In Aksu almost every symbol of the state — from police stations to telecommunications offices — is protected by barbed wire and barricades. Hotels and shopping centres force visitors to pass through metal detectors before entering. A meat and vegetable market — its stalls run almost entirely by Han Chinese migrants — is protected by security guards armed with nail-spiked bars.

Critics of Chinese government policy in the region say the steady pattern of violence can be traced to the issue of Document No 7 in the mid-1990s. Essentially a strategy blueprint for how to combat a surge in violence, the document blamed the deteriorating situation on “the infiltration and sabotaging activities of foreign religious powers”. It also called for a security-led response and tighter religious controls.

The document’s adoption ended a 1980s policy that emphasised autonomy and tolerance in Xinjiang and Tibet after the decimation of both regions’ distinct cultural and religious traditions during the cultural revolution.

Jiang Zhaoyong, a Beijing-based ethnic affairs analyst, agrees with the analysis underpinning Document No 7, arguing that “the violence has something to do with the fact that many people spend all their time praying and chanting scripts and the spread of Islamic extremism in Xinjiang”.

Human Rights Watch counters that China’s war on terror at home has been used to justify “pervasive ethnic discrimination, severe religious repression and increasing cultural suppression” in Xinjiang. Analysts also doubt the government’s claim that the East Turkestan Islamic Movement and other shadowy groups are behind many of the attacks. ETIM, they suspect, is more bark than bite and a convenient scapegoat.

“When we try to understand who these people are [there is] a complete absence of information,” says David O’Brien, a regional expert at the University of Nottingham Ningbo. “What are portrayed as co-ordinated attacks might be more localised issues.”

Wang Lixiong, a prominent government critic, says the adoption of Document No 7 signified a return to “hardline” ethnic policies. “A new tone was set and that same policy is still enforced today — political repression combined with significant economic support. It’s one hand hard and one hand soft.”

Extending grace

It is in fact an approach that dates back to at least the mid-18th century, when the Qing dynasty extended China’s borders and offered conquered peoples “grace” if they submitted to the emperor’s might.

Under Communist party rule, grace includes local government investment in refurbishing Uighur villages, transforming them into quaint tourist destinations. Ajiahan Wuxur, 68, was the beneficiary of one such project in Turpan, an oasis town near Urumqi. “Previously we could only make money selling grapes,” says Ms Wuxur, who now runs a tourist restaurant from her home. “There were fixed quotas for production and we had no other income.”

At the other end of the policy spectrum, boys and girls under the age of 18 are barred from places of worship, while bans on “unusual or strange” beards and headscarves are common. Xinjiang’s more than 800,000 civil servants, about half of whom are ethnic minorities, are prohibited from participating in religious activities. One religious leader, who asked not to be identified, says he often performed private home ceremonies for government officials. “It still happens but it must be kept secret with very few guests,” he says.

Reza Hasmath at Oxford university argues that the government’s “one hand hard, one hand soft” policy has failed to address two of the Uighur community’s longstanding grievances — poorer job opportunities despite having a higher average educational level than Han Chinese in the region, and a lack of meaningful political representation.

“These soft and hard policies don’t get to the underlying root causes of conflict in Xinjiang,” he says. “Younger generation [Uighurs] want to have their expectations met in the labour market. When those expectations are not met they turn to their ethnicity and religion. ”

According to Mr Wang, another consequence of the government’s policies in Xinjiang has been an eradication of moderate Uighur voices who advocate an approach that emphasises religious toleration and political autonomy.

Uighurs advocating this message are increasingly treated as “violent ethnic separatists” in disguise, as evidenced by last year’s prosecution of Ilham Tohti. Mr Tohti, an ethnic Uighur professor at Minzu University in Beijing and a bridge between his community and the government, was handed a life sentence for allegedly advocating independence.

“Ilham Tohti was in fact very moderate,” says Mr Wang, who himself has been banned from publishing in China and is subject to routine police harassment for his criticism of Beijing’s ethnic policies. “But the government wants you to be either an enemy or a flunky. It’s hard for them to deal with someone who stands in the middle.”

Additional reporting by Wan Li and Christian Shepherd

mercredi 14 octobre 2015

lundi 12 octobre 2015

Detained Chinese lawyer’s 16-year-old son disappears while trying to flee to US

By Tom Phillips – The son of a crusading human rights lawyer at the centre of an unprecedented Chinese government crackdown has disappeared while attempting to flee to the United States through south-east Asia.

By Tom Phillips – The son of a crusading human rights lawyer at the centre of an unprecedented Chinese government crackdown has disappeared while attempting to flee to the United States through south-east Asia.

Bao Zhuoxuan, the son of detained lawyer Wang Yu, had planned to meet human rights activists in Thailand last Sunday after slipping out of China across its south-western border with Myanmar, the Guardian understands.

The 16-year-old, whose Chinese passport was confiscated following his mother’s detention earlier this year, had intended to request asylum at the US embassy in Bangkok. A family in San Francisco had agreed to care for the teenager, whose father, Bao Longjun, is also currently in the custody of Chinese security services.

But Bao failed to turn up at the agreed rendezvous point in the Thai capital.

But Bao failed to turn up at the agreed rendezvous point in the Thai capital.

On Thursday, after days without news, activists learned uniformed officers had taken Bao and two Chinese travel companions from a hotel in Mong La, a notorious border town near Myanmar’s border with China, two days earlier.

Zhou Fengsuo, a San Francisco-based human rights activist involved in the teenager’s attempt to escape, said it was not clear if Bao remained in Myanmar or had been returned to China.

“This is like my worst nightmare,” said Zhou, who had been in Thailand to meet Bao but has now returned to the US.

“I am very worried about their safety and I want to know where they are. This is so frustrating. He is just a boy. He should not have to go through this. His parents are both in prison and he is under constant surveillance.

“All we want is for him to be able to have a peaceful life here in the US and to be able to go to school. It is so devastating.”

Bao’s mother, Wang Yu, has not been seen since she was taken from their Beijing home by security agents in the early hours of 9 July.

She was the first of dozens of lawyers and activists to be detained as part of a co-ordinated operation against China’s outspoken community of human rights lawyers. Nearly 300 lawyers and activists have been detained or questioned since the crackdown began.

Speaking earlier this year, before her detention, Wang said: “Nobody is safe under a dictatorship.”

Beijing’s crackdown, which experts say is designed to wipe out any opposition to President Xi Jinping and the Communist party he leads, has sparked international condemnation.

“Human rights and rule of law have suffered a devastating blow since president Xi Jinping came to power,” Marco Rubio, the US presidential hopeful, said this week, pointing to Beijing’s offensives against Christian churches and lawyers such as Wang Yu.

“A government that does not respect the rights and basic dignity of its own people cannot be assumed to be a responsible actor in the global arena,” Rubio added.

William Nee, a Hong Kong-based activist for Amnesty International, said Bao’s detention signalled China’s crackdown had spread beyond its borders.

Bao’s disappearance represented a “gross violation of human rights, and the internationalization of Chinese repression,” Nee said.

Speaking to the New York Times, U Zaw Htay, an official from the office of Myanmar’s president, denied his government had been involved in Bao’s apparent detention in Mong La.

“The Myanmar government wasn’t involved in any matter there,” he claimed. “We don’t know about the arrest of the Chinese lawyer’s son. Of course, Mong La is close to the Chinese authorities.”

Chinese Lawyers Call For The Abolition of Their Professional Body

RFA Uyghur Service – Dozens of Chinese lawyers have written to the country’s parliament calling for an end to legal requirements that they join their professional association, amid an ongoing crackdown on the embattled legal profession.

The letter calls for the repeal of Clause 15 of China’s Lawyers’ Law, in a gesture of protest at the government-backed lawyers’ association that they say has been instrumental in putting heavy political pressure on its members.

“This clause seriously contravenes Clause 35 of the Constitution [of the People’s Republic of China], and the right to freedom of association,” the lawyers wrote, amid an ongoing crackdown on rights lawyers and their associates by the ruling Chinese Communist Party.

“The registration of the so-called All China Lawyers’ Association (ACLA) [also] contravenes the law on social organizations, Clause 2, which states that they should be formed from the free association of Chinese citizens, and therefore was made in error and should be regarded as void,” the letter said.

Yunnan-based rights lawyer Wang Longde, who is among nearly 50 signatories to the letter, said the document would be formally presented to the National People’s Congress (NPC) by the end of the week.

“Right now we have more than 40 people who have signed, not quite 50,” Wang said. “In two days’ time, we will give a printed version of our opinion letter to the NPC standing committee.”

‘Things can’t go on’

Wang is also among a group of five lawyers including Xue Zhanyi, Wang Ligan, Mao Xiaomin, and Li Tianlingwho have publicly resigned from the lawyers’ association since March.

He said the five had resigned after failing to get their licenses renewed by the association in a process that recently became annual and mandatory.

“We issued a statement saying we were resigning from the association back in March, and we have since shared our opinions with the judicial authorities at municipal level in our local areas,” Wang said.

“There are a few of us who haven’t managed to get our licenses renewed in our annual review, and our local judicial authority has given us an authorization, so that our work is unaffected,” he said.

“We think that if the government is serious about the rule of law, things can’t go on as they are,” Wang said.

Forced to join

Fellow lawyer Zhang Keke, who engaged in a brief hunger strike last year in protest over his treatment at the hands of the Wuhan branch of the ACLA, said the association should exist to protect the interests of lawyers, not to put them in straitjacket.

“Lawyers are protesting that they are forced to join the ACLA, and yet there is no mechanism for leaving,” Zhang said.

“The ACLA should be an organization of freely associating individuals, run by lawyers, but in reality it’s run by the judicial departments of government,” he said. “It has no independent status.”

“This means that it can’t stand up for lawyers and their interests; it is on the government’s side.”

According to the Hong Kong-based Chinese Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group, at least 288 lawyers, law firm staff, human right activists, and family members have recently been detained, questioned by police, forbidden to leave the country, held under residential surveillance, or are simply missing.

While 255 have since been released, the rest remain under some form of surveillance or criminal detention in a crackdown that began with the detention of Beijing-based rights lawyer Wang Yu and her colleagues at the Fengrui law firm on the night of July 9-10, it said.

According to former Chinese judge Zhong Jinhua, who arrived last month in the United States along with his family, the crackdown hasn’t only affected lawyers who take politically sensitive human rights cases, but the entire legal profession.

The majority of lawyers are now living in fear of enforced “chats” with China’s state security police, Zhong told RFA in recent interview.

Held in secret

Wang Yu’s lawyer Wen Donghai said on Tuesday that she is still being held under “residential surveillance” at an undisclosed location, and has been denied permission to see her legal team.

“They are definitely out of line to be doing this, according to our analysis, because if she was back in Beijing, they would have to hold her in her own home [to qualify as residential surveillance],” Wen told RFA.

“But they are in Tianjin, where she has no home, and so they are able to hold her in a secret location.”

Repeated calls to the Hexi district state prosecution office in Tianjin, which is believed to be overseeing Wang Yu’s case, rang unanswered during office hours on Wednesday.

‘Troublemaking’

China’s tightly controlled state media has accused the Fengrui lawyers of “troublemaking” and seeking to incite mass incidents by publicizing cases where they defend some of the most vulnerable groups in society.

Wang is well-known in China’s human rights community, with her clients including jailed moderate ethnic Uyghur scholar Ilham Tohti and outspoken rights activist Cao Shunli, who died after being denied medical treatment in detention.

She has also defended members of the banned Falun Gong spiritual group, as well as forced evictees and petitioners seeking to protect their rights and those of women and children, as well as the rights to freedom of religion, housing, and expression.

Wang has frequently been harassed, threatened, searched, and physically assaulted by police since she began to take on rights abuse cases in 2011.

Reported by Yang Fan for RFA’s Mandarin Service, and by Hai Nan for the Cantonese Service. Translated and written in English by Luisetta Mudie.

Dalai Lama: China more concerned about future Dalai Lamas than I am

CNN, 6 October 2015

By Mick Krever – The Chinese government cares more about the institution of the Dalai Lama than the man who carries that name, the 14th Dalai Lama told CNN’s Christiane Amanpour.

By Mick Krever – The Chinese government cares more about the institution of the Dalai Lama than the man who carries that name, the 14th Dalai Lama told CNN’s Christiane Amanpour.

“I have no concern,” he told Amanpour in London, adding that it is “possible” he would be the last Dalai Lama.

The Chinese government still considers him a political leader, the Dalai Lama said, as the previous men carrying that title were for centuries. But since 2011, he told Amanpour, he is only a spiritual leader. “I totally retired from political responsibility — not only myself retired, but also (a) four-century-old tradition.”

Buddhism in Tibet far precedes the Dalai Lama, and “in the future, Tibetan Buddhism will carry (on) without the Dalai Lama.”

Decades ago, he told Amanpour, “I publicly, formally, officially — I announced the very institution of the Dalai Lama should continue or not — (it is) up to Tibetan people.”

Amanpour spoke with the Dalai Lama shortly before he was hospitalized and forced to cancel several appearances in the United States. Now back in India, he has assured his followers he is in “excellent condition.”

The Chinese government is continually at odds with the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhists. Chinese officials label him an “anti-China splittist,” alleging that he wants Tibet — now a region of China — to become an independent country.

“We are not seeking independence. Historically, we are (an) independent country. That’s what all historians know — except for the Chinese official historian; they do not accept that.”

Labeling him a “splittist,” the Dalai Lama said, fits with China’s “hardliner policy.”

“Past is past. We are looking (to the) future.”

Tibet, he said, is “materially backward,” and benefits from being part of China.

“It’s in our own interest, for further material development — provided we have our own language, very rich spirituality.”

Asked if he had a message for Chinese President Xi Jinping, who at the time was on the eve of a state visit to Washington, the Dalai Lama at first demurred.

With a laugh, he told Amanpour he’d have to think about it.

“I may say to him, Xi Jinping, leader of most populated nation, should think more realistically.”

“I want to say (to him), last year, he publicly mentioned in Paris as well as New Delhi, (that) Buddhism is a very important part of Chinese culture. He mentioned that. So I also say — I may sort of say some nice word about his — that comment.”

Nowhere else, the Dalai Lama said, is the “pure authentic” tradition of the religion kept so intact as in Tibet.

“No other Buddhist countries. So in China, preservation of Tibetan Buddhist tradition and Buddhist culture is (of) immense benefit to millions of those Chinese Buddhists.”

In one of those Buddhist countries, Myanmar, the often peaceful image of practitioners has been tarred in recent years with the persecution of — and often outright violence against — Muslim minorities, the Rohingya.

Whenever a Buddhist feels “uncomfortable” with a Muslim, or person of any other religion, the Dalai Lama said, he or she should think of “Buddha’s face.”

“If Buddha (were) there — certainly protect, or help to these victims. There’s no question. So as a follower of Buddha, you should follow Buddha sincerely. So national interest is secondary.”

“Consider as a human brothers, sisters. No matter what is his religious faith.”

“To some people, Muslim, Islam, (is) more effective. So let them follow that. We must accept that.”

The Long Arm of China: At U.N., China uses intimidation tactics to silence its critics

Reuters, 5 October 2015

By Sui-Lee Wee and Stephanie Nebehay – In a café lounge at the United Nations complex in Geneva, a Tibetan fugitive was waiting his turn earlier this year to tell diplomats his story of being imprisoned and tortured back home in China.

By Sui-Lee Wee and Stephanie Nebehay – In a café lounge at the United Nations complex in Geneva, a Tibetan fugitive was waiting his turn earlier this year to tell diplomats his story of being imprisoned and tortured back home in China.

The 43-year-old Buddhist monk, Golog Jigme, had broken out of a Chinese detention centre in 2012, eventually fleeing to Switzerland. But his Chinese government pursuers hadn’t given up.

As Golog Jigme prepared to testify in March before the U.N. Human Rights Council, a senior Chinese diplomat, Zhang Yaojun, was in the crowded café. Zhang stood just a few meters from the table where the bald monk was seated in his saffron robes.

“He just took a photo of me,” Golog Jigme said, gesturing at Zhang, who was standing with his smartphone in his hand. Zhang’s action violated a ban on photography in the halls of the United Nations, except by accredited photographers.

“When I was hiding in the mountains, the Chinese government announced a cash reward of 200,000 yuan (about $31,000) for whoever finds me,” said the monk. “Maybe he wants the cash reward.”

Zhang said later he was simply photographing the scenery and was unaware of the ban.

Golog Jigme’s caustic joke speaks to the disturbing nature of his encounter with Zhang. The surveillance of the monk, Western diplomats and activists say, is part of a campaign of intimidation, obstruction and harassment by China that is aimed at silencing criticism of its human rights record at the United Nations.

Geneva, site of the U.N.’s headquarters for handling rights violations, is a hub of that effort. The primary function of the council, whose rotating members are elected by the U.N. General Assembly, is to review countries’ human rights records.

More broadly, Beijing’s conduct here is an example of China’s growing capacity to stifle opposition in the international arena. The Communist government’s global reach is growing at a time when it is cracking down on domestic dissent and preparing a new, restrictive law on foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) operating in China. In July, Chinese authorities targeted human rights lawyers and activists, detaining or questioning 245 of them, according to Amnesty International.

Photographing and filming critics like Golog Jigme is one tactic. Others include pressuring the United Nations to deny accreditation to high-profile activists and filling up meeting halls with Chinese officials and sympathizers to drown out accusations of rights abuses.

“We are well aware of these problems, which unfortunately happen repeatedly – and are not confined just to China,” said U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein. He said he was “extremely concerned by the increasing number of cases of harassment or reprisals against those cooperating with the Human Rights Council.”

“We are well aware of these problems, which unfortunately happen repeatedly – and are not confined just to China,” said U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein. He said he was “extremely concerned by the increasing number of cases of harassment or reprisals against those cooperating with the Human Rights Council.”

Beijing is also barring mainland activists from leaving China and travelling to Geneva, where the rights council last week concluded its third three-week session of the year. Activists who speak out against their country’s rights record in Geneva have to contend with another signature Chinese tactic: coordinated interference by diplomats and delegates from Beijing-backed non-governmental organizations. These astroturf groups are known as GONGOs, or government-organized non-governmental organizations, a play on the acronym NGO.

China has an army of GONGO officials at its disposal in Geneva, especially when its record is under review. According to a U.N. database, it has 47 NGOs from the mainland, Hong Kong and Macau that are allowed to participate in meetings at the Human Rights Council. At least 34 of these are GONGOs, a Reuters calculation shows. These groups are either overseen by government ministries or Communist Party bodies, or have a current or retired party or government official as their head.

“We are well aware of, and disturbed by, the presence of NGOs that are not truly independent – again, from quite a few countries,” said U.N. High Commissioner Zeid. “But the Human Rights Council cannot do anything to prevent them from attending sessions when they enjoy official status.”

EVADING SCRUTINY

China’s campaign is working, diplomats and activists say. The ruling Communist Party has succeeded in evading censure of its rights record at the U.N. in recent years. NGOs and alleged victims of human rights abuses on the mainland are struggling to make their voices heard.

“As long as they feel the political costs of intimidating someone are lower than the benefit of hearing the criticism, the practice will continue,” said Michael Ineichen, a director at the International Service for Human Rights. The NGO supports human rights defenders. The U.N. and member states, he said, must “increase the political costs so it’s no longer beneficial for China to silence people at the U.N.”

Ren Yisheng, minister counselor in charge of human rights at China’s mission in Geneva, denied his country was engaged in intimidating activists and silencing critics. China is currently one of the 47 rotating members of the council.

Ren said China was the victim of a double standard in Geneva. “I seldom hear the (European Union) criticize the U.S. for … police brutality, Guantanamo, surveillance, the discrimination against minorities,” he said in an August interview at the Chinese mission. “I seldom hear the U.S. criticize the EU or other developed countries. Whenever they take the floor, they always focus on developing countries, including my country.”

Actually, Beijing is feeling less pressure from Western governments at the U.N. these days. No nation has brought a resolution against China since the Human Rights Council was formed in 2006. In the council’s predecessor body, the U.N. Commission on Human Rights, 11 resolutions were brought against China from 1990 to 2005. Beijing blocked them all, except in 1995 when a resolution was brought to a vote but rejected, according to Human Rights Council spokesman Rolando Gomez.

Actually, Beijing is feeling less pressure from Western governments at the U.N. these days. No nation has brought a resolution against China since the Human Rights Council was formed in 2006. In the council’s predecessor body, the U.N. Commission on Human Rights, 11 resolutions were brought against China from 1990 to 2005. Beijing blocked them all, except in 1995 when a resolution was brought to a vote but rejected, according to Human Rights Council spokesman Rolando Gomez.

Joachim Ruecker, Germany’s ambassador to the U.N. in Geneva, is the current president of the council. He said he’d heard of reports of harassment of activists by China before he became president in January. But since taking up his new post, he said he had not been confronted with any new allegations regarding China.

Asked about the photographing of Golog Jigme, Ruecker said: “This case was not brought to my attention. If I do receive such complaints, or any other susch case which might be perceived as an act of intimidation, I would follow up accordingly.”

DOMESTIC CRACKDOWN

Under President Xi Jinping, China is conducting what activists say is the worst domestic crackdown on human rights in two decades. Close to 1,000 rights activists were detained last year – nearly as many as in the previous two years combined, according to Chinese Human Rights Defenders, a coalition of Chinese and international NGOs.

The number of activists barred by China from going to Geneva is also rising. In 2014, authorities prevented 10 people from travelling to the U.N. by refusing to issue passports, confiscating travel documents or threatening reprisals, according to Thomas Shao, an independent Chinese rights activist in London. Six were blocked in 2013 and four in 2012, he said.

One of the activists prevented from attending in 2013 was veteran rights advocate Cao Shunli. She was detained in September that year at the airport as she was leaving Beijing to head to Geneva for a training session.

One of the activists prevented from attending in 2013 was veteran rights advocate Cao Shunli. She was detained in September that year at the airport as she was leaving Beijing to head to Geneva for a training session.

The next month, authorities told Cao to sign an official arrest document charging her with “picking quarrels and provoking troubles,” though she refused to sign it, the watchdog group Human Rights in China said soon afterward. That June, Cao had organized a sit-in outside the foreign ministry in Beijing, demanding that activists be allowed to participate in preparing China’s human rights report to the U.N.

Cao suffered from liver disease and later contracted tuberculosis in detention, according to her lawyer, Wang Yu. Her family and lawyers complained she was being denied essential medical care. On March 14 last year, her family arrived at a military hospital in Beijing to learn that the 52-year-old activist had died. Her death rocked China’s fledgling rights community.

The Chinese mission’s Ren said Cao refused medical treatment. She was barred from traveling because she organized protests outside the foreign ministry, said Ren. “By gathering so many people to provoke that trouble and make social disorder,” Ren said, “she had already violated the law.”

In March last year, China blocked a request by NGOs for a minute’s silence at the U.N. in Geneva to commemorate Cao’s death. One Western diplomat, who asked not to be named, said China successfully used its economic leverage to convince countries to oppose the idea.

“This gave China a new level of confidence about what they can do (at the rights council) if their core interests are at risk,” said the diplomat, who has observed Chinese officials snapping pictures of NGO members.

CHINA’S BLACKLIST

Beijing also exerts pressure on the U.N. to deny accreditation to high-profile activists outside China.

Two U.N. officials, who spoke on condition they not be named, said Beijing regularly urges the U.N. to bar at least 10 activists from attending the Human Rights Council sessions. Beijing brands these people as “splittists, terrorists or criminals,” one of the officials said.

Those on Beijing’s black list, the officials said, include the Tibetan spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, and two leaders of the World Uyghur Congress, Dolkun Isa and Rebiya Kadeer. The most recent instance was ahead of September’s council session, they said.

The two U.N. officials said the organization tells Beijing that these activists do not pose a security threat. This year, Isa said he attended sessions in March, June and September, but Kadeer did not.

The two U.N. officials said the organization tells Beijing that these activists do not pose a security threat. This year, Isa said he attended sessions in March, June and September, but Kadeer did not.

Ren said China sends a “note verbale,” or diplomatic communication, to the council when it sees that Kadeer or Isa are attending. China has evidence that the World Uyghur Congress is linked to terrorist activity and this constitutes a “threat for the Council,” he said. Council spokesman Gomez said the U.N. had “never prevented” the Uighur body from attending meetings in Geneva. The Uighurs are a Muslim ethnic minority that resides largely in western China.

The U.N. takes measures to protect some China critics. Isa of the World Uyghur Congress said he was shadowed by a U.N. guard during his visit to the council in October 2013, when China was under scrutiny as part of a periodic review of its rights record. Two veteran U.N. security guards confirmed that Isa is one of the Chinese activists who are regularly assigned special protection.

For those activists who make it to Geneva, the Chinese state is never far away. Besides Golog Jigme, seven other activists who have spoken out against human rights abuses in China told Reuters they have also been photographed without their consent at the council.

A foreign passport is no protection. Ti-Anna Wang, a Canadian citizen, is the 26-year-old daughter of jailed Chinese dissident Wang Bingzhang. She said she was unnerved in March 2014 when an official from the China Association for Preservation and Development of Tibetan Culture, one of Beijing’s GONGOs, photographed her during a meeting of the council.

“He had a tablet that was hidden inside his jacket and the camera part was pointing out,” Wang said.

The Tibetan culture association describes itself as an NGO. But according to its website, many of its top executives are also government or Communist Party officials. In 2010, Jia Qinglin, then a member of the party’s Politburo Standing Committee, China’s supreme ruling body, told the association’s members that they had to “expose and criticize the reactionary nature of the Dalai (Lama) clique splitting the motherland.”

Two letters reviewed by Reuters show that in Ti-Anna Wang’s case, the U.N. council took action. According to a letter dated March 24, 2014, a Chinese delegate of the Tibetan association, Yao Yuan, had his accreditation revoked by the U.N. for taking the pictures. The lack of a response from China to that letter prompted a second letter two months later, saying that Yao’s badge and accreditation would “remain revoked until further notice.” Wang isn’t referred to by name in the letters, which were written on official U.N. stationery.

The China Association for Preservation and Development of Tibetan Culture did not respond to questions about the incident.

Activists say China is sometimes using sheer numbers to stymie criticism. Ineichen, of the International Service for Human Rights, said he watched a Chinese diplomat “directing individuals who were posing as NGO staff, to basically occupy as many seats as possible,” at a review last year of China’s record on economic, social and cultural rights.

‘I MEANT NO HARM’

It was three hours before Golog Jigme was set to deliver his speech at a side event of the Human Rights Council session when he spotted Zhang photographing him in the Serpentine café. The café is situated two floors below the domed room where the council meets.

After snapping the picture, Zhang walked away and bought a sandwich, taking it outside to a terrace. The following day, as Zhang emerged from a council session, a Reuters reporter approached the Chinese diplomat and asked him about the incident. He denied photographing the Tibetan. Zhang said he was simply taking a panoramic shot of the space and was unaware it was against U.N. rules.

Zhang said he was based in Beijing but declined to give his title. He is listed as first secretary in the Department of International Organizations and Conferences in China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, according to the roster of delegates for the Human Rights Council session that Beijing submitted to the U.N.

“I meant no harm,” Zhang said, taking out his phone and quickly swiping through the stored images. “I did not take his picture, I can definitely tell you.” He declined to show Reuters the images.

Ren offered a different explanation: “The Serpentine bar has a big glass window,” he said. “He might be taking the view of Mont Blanc. Who knows? I mean, there happened to be a monk sitting there.”

In Geneva, Golog Jigme was the first to speak at the side event. Two Chinese diplomats and a representative from a Chinese GONGO were in the audience. The monk described how he was detained and tortured.

The State Council Information Office in Beijing did not respond to questions about Golog Jigme’s arrest or his allegations of torture.

MURDER CHARGE

After Golog Jigme spoke, rights activists followed with speeches criticizing China’s treatment of Tibetans, Uighurs and ethnic Mongolians.

The moderator then called for questions. Liu Huawen, a representative from an organization called the China Society for Human Rights Studies, raised his hand.

“We should not just talk about your story, but we better have solid evidence and resources and information,” Liu said in a challenge to the monk’s account. Other countries also deprive criminals of political rights, Liu said.

Founded in 1993, the China Society for Human Rights Studies describes itself as the “largest national NGO in the field of human rights in China.” It’s headed by Luo Haocai, a former vice-chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, China’s top parliamentary advisory body.

Liu told Reuters he did not have much contact with the Chinese mission in Geneva. “We are not so stupid as to bully minorities,” he said.

Golog Jigme says his troubles started after he made a documentary with a Tibetan filmmaker exploring how Tibetans felt about the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

The footage was smuggled out to Switzerland, where it was made into a film called “Leaving Fear Behind.” Soon after the Olympics, the Tibetan monk was arrested by Chinese authorities on charges of divulging state secrets and inciting separatism, he said.

On March 16, in the building of the U.N. Human Rights Council in Geneva, he described in detail how Chinese security officials beat him severely many times, breaking his ribs and dislocating his knee joints. His voice rising, he spoke about how he was chained to a “tiger chair” – a chair that kept his hands and feet shackled – for 10 hours when he was detained the first time.

He showed a Reuters reporter indents on his wrists, which he said were scars left from being chained to the “tiger chair.” Reuters was not able to independently verify Golog Jigme’s account of his treatment.

Released after seven months, he was detained again in 2009 for four months, he said. In September 2012, he was arrested again and accused of instigating a wave of self-immolation protests and revealing state secrets. Since 2011, 142 Tibetans have self-immolated in protest against China’s policies in Tibet, according to the International Campaign for Tibet.

While in custody, Golog Jigme said police officers told him they would transfer him to a military hospital to receive injections, even though he was not ill. The monk said he believed they intended to kill him, so he decided to escape. On September 30, 2012, he was going to the bathroom when he found a pin on the ground, he said.

He used the pin to open his leg cuffs, fled the detention centre and hid in the mountains of Gansu province for two months. From the mountains, Golog Jigme said he first headed to the western province of Qinghai and then to exile in India, before arriving in Zurich in January this year. The monk said he did not want to divulge all the details of his escape route.

The foreign ministry in Beijing and the governments of Gansu and Linxia – the city where Golog Jigme was detained – did not respond to questions from Reuters.

While hiding in the mountains after his jailbreak, Golog Jigme heard that he had been charged with murder. Chinese authorities are charging some Tibetans with murder if they are accused of inciting self-immolations, according to a document issued jointly by China’s top court, prosecutor’s office and public security authorities.

The accusation was baseless, the monk told the Geneva audience. He considered setting himself on fire in front of a police station, he said, “as a protest and to prove my innocence.” In the end, he decided to keep working for the Tibetan cause, “and escaped into freedom.”

Inscription à :

Commentaires (Atom)